What major biochemical insights then-- related to the origin of life --- have we gained since Nobel Laureate Melvin Calvin's 1969 book Chemical Evolution summarized the fashionable ideas of that decade?

(1) Primordial Catalysts Were Probably Not Proteins

In the 1960's, RNA's role as a catalyst and replicator was greatly underestimated. Unaware of retroviruses, or at least of their reproductive mechanism, biochemists believed that information only flowed from DNA to RNA, and they perceived proteins to be the only biological catalysts. After the discovery of ribozymes revealed that tertiary RNA molecules could speed up their own production, it was hypothesized that these were life's first catalysts because they could have evolved from single-stranded RNA molecules, which are structurally simpler than both DNA and proteins.

But the current popular notion that RNA was essentially the sole primeval replicator and catalyst has also come under attack. As an alternative, the first catalysts may have also included inorganic ions. Hydrothermal vents are rich in iron (II) sulfide (FeS) and nickel (II) sulfide, both of which can speed up biochemical reactions. In existing hydrothermal bacteria and archaebacteria, these compounds are part of protein complexes, but the ions are the reactive catalytic centers for a remarkable exergonic reaction. Hydrogen gas from the vents combines with dissolved carbon dioxide in the sea (and an acetyl-less CoA ) to produce water and acetylCoA (a key molecule involved in releasing energy from sugars; in fatty acid synthesis etc). The overall reaction releases 59 kJ of free energy for every 2 moles of fixed CO2, enough to drive the synthesis of ATP.

Another argument against RNA exclusivity from Lane, Allen and Martin is that each time RNA makes a copy of itself in a "primordial soup" its concentration drops so the rate of reaction can only be maintained if nucleotides are continuously replenished. This brings us to the issue of energy.

(2) First Energy Source Likely Involved Proton Gradients

In the same way that a room only remains tidy and dustless with continuous effort, life forms are capable of maintaining order only in the presence of a continuous energy supply. Even before life arises, the required conversions of small molecules to larger ones are endothermic. Whereas the original hypotheses were careful enough to exclude oxygen from the original mix because an oxidizing atmosphere would break up newly made molecules, the irony is that the proposed energy sources, ultraviolet and lightning, would also destroy newly synthesized molecules. The excessive heat and low pH's from deep, volcanic hydrothermal vents do not lead to a viable energy alternative.

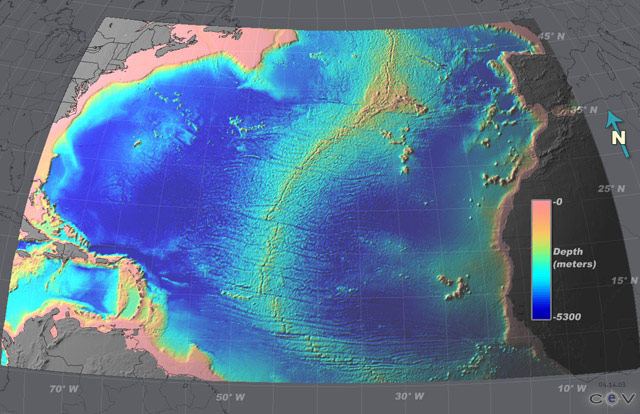

But Lane, Miller and Allen point out that there is another hydrothermal vent which gets its heat from the mid Atlantic's tectonic boundaries, known as the Lost City, where olivine mineral (a combination of magnesium and iron silicates) turns to serpentine (hydroxylated iron and magnesium silicates).

But Lane, Miller and Allen point out that there is another hydrothermal vent which gets its heat from the mid Atlantic's tectonic boundaries, known as the Lost City, where olivine mineral (a combination of magnesium and iron silicates) turns to serpentine (hydroxylated iron and magnesium silicates).

This is the source of hydrogen gas used by the previously mentioned bacteria to "fix" carbon dioxide into acetyl, a part of a vital metabolite. The hydroxides formed are not inconsequential because, with the help of simple membranes, they provide a natural pH-gradient, essentially a voltage, one that was more pronounced in ancient seas due to CO2 concentrations that were 1000 times higher than their modern counterpart. Remarkably that gradient is comparable to the one created by the biochemical processes in today's cells.

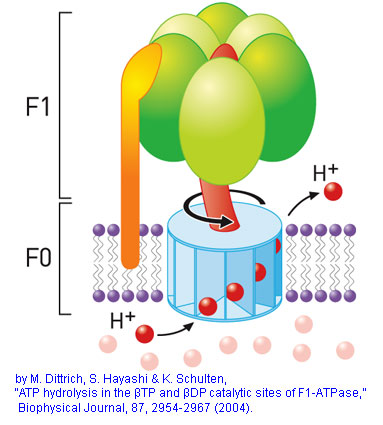

Forty years ago, this idea that chemiosmosis was the energy-provider for earth life's first cells could not be put forth because no one understood how the universal reaction-facilitator, ATP(adenosine triphosphate), was made from ADP(adenosine diphosphate). But given that proton gradients power ATP production in all kingdoms of life: in respiration, photosynthesis and in rotating motors of bacterial flagella, the hypothesis is now plausible. The enzyme ATP synthase is a molecular machine whose "blades" are rotated by H+ that are put in motion by coulombic repulsion. The enzyme-portion attracts and combines ADP with a phosphate group and the spinning nanomachine releases the ATP.

DiMauro has spent 10 years working on the chemistry of 1-carbon amide formamide (H2NCOH), subjecting it to a variety of conditions and mineral catalysts. He has produced all four nucleic acids and a variety of carboxylic acids. What works best is when he uses a pH of 9 to 10 and temperatures in the 80–160 ◦C range, conditions that are found in non-volcanic hydrothermal vents.

(3) Knowledge of New Bacterial Kingdoms Downplays Role of Fermentation In First Cells

The authors of How did LUCA make a living? Chemiosmosis in the origin of life. BioEssays. January 2010 refute the popular notion that fermentation was used by the first cells to release chemical energy from food molecules. Aside from the idea that fermentation seems to be a derived chemical process, when comparing bacteria to archaea, there are also major differences in the gene sequences of fermentation enzymes. On the surface they seem like similar processes, but in reality the release of energy in oxygen's absence evolved separately and independently. It's essentially convergent evolution, the way Old World Euphorbia and New World cacti have similar adaptations but are not related.

Clostridia-type fermentations (Clostridia are sulfite reducing bacteria that include tetanus-producing bacteria), which represent ancient lineages, actually involve chemiosmosis, which of course exploits ion gradients across the cytoplasmic membrane and rotor–stator type ATPases (enzymes that cleave ATP to place a good leaving group on otherwise nonreactive molecules). The same is true of fermentation in most free-living anaerobic bacteria.

Conclusion

Writing in 1969, Calvin wrote:

As long as we are limited to biology as it is on the earth, it is going to be difficult for us to be sure that such a system occurred in the way described in this book. We shall have to find other places in the universe, preferably nearby, in which this process is going on and has not gone all the way, so that we can observe it at some other stage of its development. this is why I am interested in lunar and planetary exploration.In four decades no such places have been found yet, but at least something esoteric has been discovered at the bottom of our own oceans. It's far from direct evidence, which of course eludes everyone because the molecular precursors to primordial life left no traces. But along with more detailed knowledge of biochemistry, the Lost City has inspired hypotheses that bring us closer to a non-fictitious narrative of our chemical history.

SOURCES:

- William F. Martin Edited by Miguel Teixeira and Ricardo O. Louro Hydrogen, metals, bifurcating electrons, and proton gradients: The early evolution of biological energy conservation Febs Letters Volume 586, Issue 5, 9 March 2012, Pages 485–493

- Nick Lane, John F. Allen, William Martin. How did LUCA make a living? Chemiosmosis in the origin of life. BioEssays. January 2010 (whole article can be read free of charge)

- Michael J. Russell, William Martin. The Rocky Roots of the Acetyl-coA Pathway TRENDS in Biochemical Sciences Vol.29 No.7 July 2004 (whole article can again be read free of charge)

- Calvin, M. (1969). Chemical evolution: Molecular evolution towards the origin of living systems on the earth and elsewhere. Oxford: Clarendon Press. QH325 .C26